Authors: Lars Thuesen, Mark T. Munger

Change Leaders and Positive Deviance Facilitators

Spearheaded by UN Women and with the generous support of UNDOCO’s Delivering Together Facility the Palestine Innovation Labs was initiated during the spring of 2018. UN Women special representative at the time Ms. Ulzii Jamsran said:

“The Lab format is helping UN colleagues, partners and communities to accelerate joint learning, testing and implementing innovative tools that ensure sustainable change. This is a genuine way to do development differently”.

A team of change leaders and facilitators from WIN (The Welfare Improvement Network – see: http://win-org.eu/english/index.html) has helped design and accelerate delivery of the Lab. 5 UN agencies have been working intensively with their local partners and communities in the West Bank and Gaza to test and implement the Positive Deviance Approach as the main approach, but also complexity science, adaptive leadership, design thinking and narrative approaches have been part of the methodologies that have been introduced.

The Innovation Lab methodology is a well-documented approach to create, accelerate and sustain change. In the Lab relevant cross-sector stakeholders are given a mandate to experiment, prototype and implement micro actions and change. It creates a safe space for innovation and experimentation to happen. The idea is ‘to act your way into a new way of thinking’. In other words, you create a greenhouse for change and innovation. The main approach of this Lab is the Positive Deviance Approach, where communities through a co-creation process discover successful behavioral strategies that are already practiced by community, so peers and can learn from them. In the UN Palestine Innovation Lab, the following principles have been applied.

Communities flip problems to look for solutions and ask if someone is already performing and have better outcomes than their peers (see the illustrations below).

All relevant community members are involved. This means that community members are the experts and play a crucial role and professionals act as experts in being non-experts and are having a role as facilitators.

Communities jointly discover both what the champion behaviors are and how they are being practiced. If the ‘how’ is not determined, it is possible for other community members to learn from the champion behaviours.

Communities act their way into news ways of thinking instead of thinking their ways into new ways of acting. It is easier to practice than tell.

Data and metrics are crucial and owned and monitored by the communities. This means that community-based monitoring tools, e.g. community scorecards are developing and maintained by communities to keep track of progress and upscaling.

6 ongoing projects have been part of the Innovation Lab and are currently using the Positive Deviance Approach to discover and implement sustainable solutions to complex social problems:

UN Women in the West Bank and Gaza: Men and women for gender and equality regional program to work on reducing early and relative marriages, improving women’s inheritance rights, and men and women sharing household work and raising children.

UNDP in Gaza: Learning from young students and future community leaders in the Al Fakhoora project and how they engage with communities

UNICEF in East Jerusalem: Reducing violence and harassment among male students at Masqat school for males in Bethany.

UN HABITAT in the town of Barta’ Area C, West Bank: Developing a local planning council

UNODC: Engaging and learning from sport coaches and young women in sports activities in the West Bank.

UN Women (Gaza and West Bank): Decent work for women to learn from women entrepreneurs and their supporters.

Though the projects are still at an early stage, it has been amazing to see how community engagement and ownership has grown over the last months when ‘what already works well’ are being discovered. And many of the projects dissemination and upscaling activities are happening through community meetings where peer to peer learning is taking place. The experiences and stories are very rich, and it is not impossible to share all the treasures here. Let us highlight a few wonderful stories from the field.

In the ‘Men and women for gender and equality project’ spearheaded by UN Women there are examples of PD behaviours that are now being disseminated and upscaled. For example, religious leaders in the southern part of Gaza that actively speak up against early marriages have been identified. One Imam encourages young people and their families to avoid early and marriages among relatives during the Friday prayers. One result has been couples who decide to postpone marriage until the age of 18. The Imam also speaks with other religious leaders to motivate them to speak against and avoid early marriages. Also, community leaders avoid giving permission to couples that want to marry under the age of 18. Another example is a well-known radio host, Yousef Nassar that has several radio shows. During his programs he speaks up for gender and equality. He has promised to continue the work on promoting gender equality in his radio shows and link with CBOs in Gaza to talk about the issues. A final example is an older man who greeted us warmly during a workshop in Gaza:

“Before joining this project, I did not know about shared household work. I used to come home and shout at my wife, because the work was not completed. Now I have understood how hard household work is and how long time it takes. I am sharing the work with my wife now. And you know what. This is the first time I really respect my wife”.

Four areas of positive champion behaviours have been identified in the men and women for gender equality regional programme. Here is the programme poster where the four themes areas illustrated by small envelopes that can be opened to learn more about the positive champion behaviours.

Keeping track of how the positive champions’ behaviors are being disseminated and upscaled is very important. As professionals we usually define indicators for success and impact. It is in our DNA. A positive deviance innovation process involves community stakeholders deeply in defining criteria for success and performance indicators. This is usually done by developing community scorecards that can be used as supporting structures for dialogues among community members as the monitor the progress of change.

For example, during workshops in Gaza and the West Bank local NGO’s and community members developed quantitative indicators – so-called community scorecards and tools that will help them keeping track of upscaling of positive champion behaviours. They also agreed to meet monthly or bi-monthly with updated scorecards to discuss progress. As a way of dissemination and upscaling community members also arranged home visit in gender balanced families, where husbands and wife shared household work to learn from the positive examples.

NGO’s and NDC Programs officer Azhar Besiaso develop indicators that can help communities keep track of dissemination and upscaling of positive champion behaviors in Gaza to help men and boys promote gender equality.

Draft scorecard developed and presented by community members – not monitoring and evaluation experts

Another example is the Al Fakhoora Dynamic Futures Programme spearheaded by UNDP in Gaza. The project aims at building a cadre of educated and trained leaders who are civic-minded, intellectually able, and professionally skilled to become community, business, and national leaders of the future. The programme targets Palestinian postsecondary students of underserved backgrounds, avails opportunities for them to actualize their potential by overcoming socioeconomic, political and cultural limitations and enabling them to become productive members in the society. In the spring of 2018, when the Innovation lab was established, around 30 young postsecondary female and male students of underserved backgrounds were identified, who exhibited behaviours beyond the norms of their community.

With marginalized rural or low-income areas within the Gaza Strip, women’s roles are still thought to be limited to the traditional role. Limited spaces of discussion and high gender sensitivity still affects how both women and men interact with each other, how they can accept each other’s behaviour or belief that women can have a leading role in the community, as well as change in men’s believes and inclusion.

Here are a few stories from the field:

Mohammed Zourob began to work with and respect female students

Mohammed lives in a rural conservative community, moved from Saudi Arabia to Gaza, where he has minimum contact with females, no equal communication or discussions, and the community believes in that the role of women is limited to being housewives. Mohammed was part of the Al Fakhoora’s training on the Art of Dialogue and Facilitation where the working groups were gender mixed (men and women). His engagement with Al Fakhoora programme showed him that female students were capable and equal in terms of being outstanding partners in a group. Mohammed now believes in the inclusion of women and encourages engagement of both young women and men in the community. He is an agent of change, and he is encouraging his colleagues, family members, friends and community members to follow the new norm (gender inclusion, engagement and interaction within their community in Gaza. Mohammed said: “Al Fakhoora changed me, and I have more respect to women and will treat them as equal as men”. Now Mohammed’s respectful behaviour is an inspiration for others.

Randa Al Dwoodi initiated a community book club

Randa was raised in Gaza and her mother is a school headmaster. She grew up in a house where they believe in gender equality and empowered. Randa faced challenges in her school and community. When she joined the Al Fakhoora programme, the same challenge occurred at the university. Randa is an active young woman who networks with both female and male students. She decided to initiate ‘Kawkaba’ to encourage her friends to read (read a book weekly and discuss it, the target are men and women between 16-30 years). In this way she has been able to engage community members.

Mohammed and Randa sharing their stories

The Al Fakhoora programme already has a strong measuring and evaluation plan. However, a new plan has been drafted by the students that can help keeping track of progress. The plan is to upscale the approach and currently students are working on the dissemination plan and drafting the monitoring framework with relevant indicators.

Discovering Positive Champion behaviours and drafting community scorecards at the new Al Fakhoora house

Innovation workshop with Al Fakhoora students

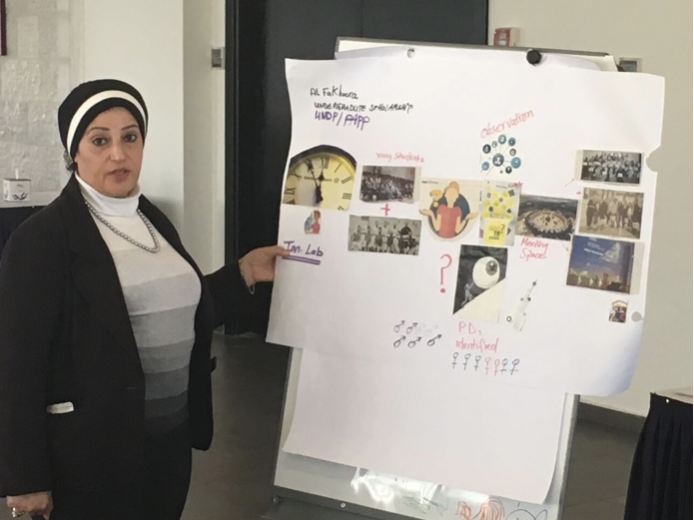

UNDP Project manager Maha Abusamra reflects:

“It is new way of working, learning while doing, discovering what works well and what did not work. It is important to be a good listener and watch closely how they are working, and the dynamic of the community when they get together to discuss the issues/cases. I am amazed by how the students have been able to engage community members in very meaningful activities, and I look forward to sharing their stories. I learnt that the best solutions are the ones that are coming from within the community, and it is sustainable, realistic, applicable and repeatable. The positive deviants felt happy when we acknowledged their behaviour as positive and felt empowered and full of energy to continue and disseminate what are they are practicing as a normal behaviour. The UN innovation Lab is helping us as members from the different UN agencies to work differently: we are more engaged, interactive, and supportive to each other’s projects. I think this narrowed the gap between the members and helped to facilitate and improve our work relations at both personal and professional levels. This is the incentive for more UN joint projects. It is working well, and in a new way, where all are engaged”.

UNDP project manager Maha Abusamra presenting the Al Fakhoora project

The UNODC project manager Lavinia Spennati reflects:

“It brings ownership back to the communities, which become the leaders of the action, while at the same time it responds to the technical needs of donors and UN agencies. The Lab was a space that encouraged us to experiment such new ways and provided concrete support beyond theoretical concepts.”

UNODC project manager Lavinia Spennati explaining the process during an innovation workshop

My colleague Mark T. Munger and I have been facilitating the Innovation Labs. Here are a couple of reflections from a facilitator point of view:

Nurturing innovation under conditions with serious constraints

The Positive Deviance approach always focuses on positive outliers that succeed despite constraints or lack of resources. But it is especially interesting to reflect upon whether the situation in Palestine with all the political constraints makes the approach even more relevant and applicable. The answer is: perhaps, yes. As facilitators we found extremely motivated community members, both positive champions and other community members who work intensively to solve serious problems. It seems as if people have no time to waste and jump immediately to do good work.

2. The Innovation Lab methodology as an accelerator of social change

One principle we often use in positive deviance projects is: you have to go slow to go fast. That is often very true. In the Innovation Lab process is has been interesting to see how fast you can go together if you design meetings, workshops and collaborate in ways that enable people to communicate, share, learn and reflect. As Innovation Lab designers we are certain that this way of working helps accelerate and sustain social change.

3. Enlarging solution spaces by distributed ownership at multiple levels

One final reflection is about how we as facilitators managed to enlarge solution and innovation spaces by engaging relevant partners and community members at all levels. Both in terms of psychically bringing them together to have conversations about change. But also, in terms of changing perspectives and mind-sets. For example, many UN participants are traditionally functioning as liaisons between donors and local implementers. In the Innovation Lab process UN Lab participants are becoming very involved in the implementation. Similarly, positive deviants have been excellent in sharing how they have overcome challenges and their success stories, and now they are changing roles to become trainers and influencers so other community members can learn from them.

As change leaders and positive deviance facilitators we are enjoying and very honored to be part of this important change journey.

For more information please contact: change leaders and positive deviance facilitators [email protected], [email protected] or UN Women Innovation Lab programme manager [email protected] or UNDP programme manager [email protected]