Author: Christina Simmons 1

Positive Deviance Consultant

Abstract

The children of the Chuukese and Marshallese migrant communities (together known as Native Micronesians) based in Hawaii, U.S.A., have struggled to achieve educational success in school. About half of all Native Micronesian students drop out before graduating high school, one-third are chronically absent, and truancy, tardiness and run-ins with the law are common. Highly family-oriented, proud, and religious, the Native Micronesians of Hawaii feel uprooted from their matrilineal, community-centered, and agrarian lifestyle and transplanted in a fast urban culture that privileges a “me”-orientation. Not surprising, families and their young ones struggle to acculturate. Educators and service providers blame the families for their children’s failure in schools. The Family Center of an NGO (from now, FC) in Hawaii decided instead to focus on the strengths, assets, and resourcefulness of the Native Micronesian families. Using the Positive Deviance (PD) approach, FC launched the Sundays Project, turning the educational tide. As a result, Native Micronesian families are now deeply engaged in, and contributing to, their children’s academic success.

A Chuukese mother who participated in the FC's Sundays Project recounted what changed as a result of the Positive Deviance process:

It’s like a door opened ... [The project] taught us our responsibilities as mothers.... we also realized our failures: we don’t make time for preparing the children, we don’t make time for sitting down with them and helping them with their assignment. The child comes and says ‘mama, here is my homework. Sign it.’ That’s all I did. Our thanks to the project because now we understand our responsibilities to our children.

This poignant quote reflects how the Positive Deviance (PD) process with Native Micronesian families evoked a collective ethos of parental involvement in the academic success of their children. All the more meaningful for the Native Micronesians believe: “If I learn you learn, if I fail we fail.”

The year was 2007. I was in my office staring out at the kids walking by. A tall pretty brown-skinned girl with a woven coconut leaf flower over her right ear walked past me. She glanced over her left shoulder towards Tower B, ensuring family elders were not watching. Pausing around the corner she rolled up her skirt to reveal her knees. Next she peeled off her long-sleeved plaid flannel shirt revealing a pink tank top announcing Spunky in rhinestones across her chest. She stuffed the flannel shirt inside her backpack atop her schoolbooks. The flower was readjusted and firmly set in front of her ear. She was now ready for her other life— as a Marshallese immigrant student attending a high school in Hawaii.

This morning transformation among high schoolers was a common sight at the Kuhio Park Terrace public housing in Honolulu. Sometimes in the afternoon, I would watch the same tall pretty girl returning from school with her friends, laughing and talking. I could not distinguish her from her peers.

A year later in 2008, I met this girl’s mother and grandmother at the first Marshallese Education Day celebrations where she was honored for consistently earning a grade point average (GPA) of 3.0 (out of 4) or higher. In greeting her elders, I did not tell them about the daily wardrobe changes I witnessed near my office. The family spoke Marshallese as adult Native Micronesians usually speak little English. Most of them live in low-income housing, work entry-level jobs, and struggle to make ends meet. The grandmother endured serious health issues, possibly associated with the intensive nuclear testing by the U.S. government on their atoll home islands. Although they embraced their new American home, they struggled to maintain aspects of their culture—clothing, food, music, religion and, above all, relationships. While for most immigrants, life at home was at odds with expectations at school, remarkably, this young girl was able to bridge both worlds with success.

The girl, a positive deviant, sparked my interest. She defied the stereotype of a Marshallese high school student. While half of Marshallese and Chuukese students did not graduate high school,2 this girl had beaten the odds. I wondered what enabled her to become one of a handful of Native Micronesian students destined for college, given only 1 to 2% of them end up earning a bachelor’s degree (Levin, 2015)? What is going on in her home that is different than a typical Native Micronesian household? Are there some household behaviors in her home that can be replicated in another?

These questions and contemplations helped launch the PD Sundays Project on the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

Native Micronesian Migration to the U.S.

The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) consisting of the states of Chuuk, Kosrae, Yap, and Pohnpei, and also the Republic of the Marshall Islands and Palau, have a unique relationship with the United States under the Compact of Free Association (COFA). Together they represent a scattering of postcard pretty islands and atolls strewn across the Western Pacific where islanders believe that the ocean, which separates them, actually connects them. While there exist cultural similarities, each island group has its own history, language, legends, dress, foods, and crafts. There is a tendency to lump these diverse people together as “Micronesian” which can be confusing. For this chapter, I use the term “Native Micronesian” to describe the work done with a mix of Chuukese and Marshallese families, and “Chuukese” and “Marshallese” when making specific attributions to a particular cultural group.

After World War II, the U.S. created and administered (from 1947 to 1986) a ‘strategic’ TTPI (Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands; later turned into COFA), allowing migrants from the region to enter the U.S. without a visa. COFA migrants can attend school and live and work in the U.S. This unique relationship between the U.S. and Western Pacific island countries is a direct result of the U.S. performing over 700 nuclear tests (on air, land, and under the sea) in this region between 1946 and 1962. In return, the U.S. pays remittance to each country government and provides security through a strong military presence (Society, 2015).

Attracted by economic and educational opportunities, access to high quality medical care, and cognizant of rising sea levels, thousands of Micronesian families with school-aged children are moving to Guam, Hawaii, and the U.S. mainland (Agency, 2013). Records indicate that a total of 6,963 Micronesian students enrolled in the Hawaii Department of Education (Moyer, Acting Director, Data Governance and Analysis Branch, 2015). This increasing influx of migrants puts a heavy strain on Hawaii’s educational system.

While most teachers try their best to engage Native Micronesian students in the classroom, some label this newest migrant group as an educational failure. School staff cannot understand why parents don’t show up at school events, or help students at home. They believe, mistakenly, that parents do not care about the future of the next generation. Further, Native Micronesian children face discrimination (Jetnil-Kijiner, 2013), and parents feel unwelcome in their child’s school. Yet, parents hold Hawaiian schools in high esteem, believing their children are privileged to be in attendance.

Enter Positive Deviance

As Hawaiian schools accommodated the influx of immigrant students, I and the staff of the Family Center (FC) believed this problem of high academic failure would persist unless the Native Micronesian community was invited to be part of the solution. Meetings with Chuukese and Marshallese community members suggested that while families hold education to be essential, certain normative household behaviors were negatively impacting the students’ ability to succeed in schools (Heine, 2002). This disconnect between educational values and action motivated FC staff to look for assets and strengths in the community that could address this chasm. Untapped strengths among the Native Micronesians included deep connections between family, church, and community; rich traditions with multi-generational families caring for one another; and a generosity of spirit with an accompanying belief that “we” comes before “me.” These strengths represented ripe gifts to initiate a Positive Deviance project, and represent the reasons responsible for its current continuance (in 2016).

Working with Native Micronesian community members we discovered positively deviant individuals—those who had high attendance, low tardiness, and were succeeding academically against all odds (such as earning a college degree). We also discovered students who came into the Hawaii school system speaking little English but somehow were able to quickly graduate out of the English Language Learner program and be mainstreamed into regular classrooms. We also came across families that had strong supportive structures to ensure their children were successful. In sum, educational success was all around us, but invisible to our problem-focused lens. We needed to readjust our lenses to discover what was working, to unearth the hidden solutions.

Starting in 2008, members of the Native Micronesian community began to meet under the Family Center’s umbrella with the purpose of tackling the problem of high rates of school dropouts. With a solution-focused lens, the community conversations sought answers to the following question: What are the family practices of those Chuukese and Marshallese households whose children are succeeding in schools? Just posing this question led to new insights on what made educational success possible. Numerous stories came to the fore, including narratives about students who, against all odds, found social supports from an extensive kinship network, or the local church, or from community mentors.

Over several such conversations, a group of Native Micronesian leaders, parents, and committed community members came together to create the Seven Sundays Project (translated from Chuukese into English). The Chuukese community identified seven key concepts that helped the students succeed. The idea was to disseminate these concepts through churches on Sundays, hence the name Seven Sundays Project. Later, an eighth concept was added and the project began to be simply referred as the Sundays Project (see Table 1).

Table 1: The Concepts that Guide the Sundays Project

The Importance of the First Day of School.

Parents Love is the Greatest Treasure.

Help Your Child Make the Most of School.

Education Begins at Home.

Parent Involvement Continues at School and in the Community.

Read to Your Child Every Day.

Father Plays an Important Role in a Child’s Life.

How Do I Know How Well My Child Is Doing in School?

When the Sundays Project was launched, a few influential deacons in some Native Micronesian churches delivered the program lecture-style, emphasizing the knowing. The focus was on information-transfer of the concepts, not on doing. While hundreds of families and children were reached this way, little happened with respect to the actual practice of what was being preached.

As Churches are at the center of spiritual and social life for many Chuukese and Marshallese, they represent a powerful vehicle for delivering programs and activities. However, most Native Micronesian communities do not have their own permanent churches but rather rent space from more established local churches. As Church service tends to last several hours (if not all day), renting space for even longer periods was cost-prohibitive and, time-wise, was far too much to ask of families, especially those with young children. The project had to adapt quickly. For instance, gathering times were changed to weekday mornings or evenings, and held at locations close to densely-populated public housing areas. Mothers could drop their kids off at school and attend meetings with infants. A Sundays Project session lasts two-to-three hours and the total curriculum for families runs for between 12 to 15 sessions (a total of 35-45 contact hours). As participants gained in confidence, meetings began to include librarians, teachers, and school administrators.

Right from our inception, we at the Family Center considered ourselves a learning community. When we got started in 2008 with family sessions, we discovered that no participant could read a standards-based student report card issued by an elementary school of the Hawaii Department of Education (HDOE). None of the parents knew what a rubric was, or how learner outcomes were used to grade their child’s progress. This recognition led to the addition of the eighth concept to the original Seven Sundays Project: How Do I Know How Well My Child is Doing in School? We also learned that the eight conceptual touchstones of the Sunday’s Project needed to be specific yet ambiguous enough to allow for the emergence of adaptive community solutions. Such was especially important as our PD project on educational success was trying to cater to four cultural constituencies—the Chuukese, the Marshallese, the local Hawaiian culture, and HDOE officials. For this reason, the unique community solutions of each group needed to be first identified, and only later, once trusting relationships were in place and parents had gained confidence in the approach through the practice of newly-identified behaviors, for other elements to be added.

A Serendipitous Flip

This project began like so many others—as a way to increase awareness about the seven concepts in the Native Micronesian community, believing that increased knowledge among parents about why they should be more involved in their children’s education, will lead to attitudinal change, which, in turn, would lead to changed practice. Even though I was trained in this KAP (knowledge-attitude-practice) process of behavior change, my experience suggested that it was neither a very efficient or effective process. During the launch of the Sundays Project, I was searching for alternative pathways to change. At FC, we were hungry to embrace a more effective process.

I learned about the PD process several months into the creation of the Sunday Project. I stayed at home one day in late 2008 ill in bed reading Atul Gawande’s book, Better. Here-in, Gawande’s description of Jerry and Monique Sternin’s impressive work to combat widespread malnutrition among Vietnamese children stood out for me. It was like a light bulb had turned on. I jumped out of bed and called my FC colleagues, emphasizing that the positive deviance approach could significantly improve our implementation of the Sundays Project. In Vietnam, the success of the PD project rested on flipping the KAP process on its head, believing that if one began with changing practice, changes in attitudes and knowledge would follow i.e. PAK. From that day on in our Sundays Project, we beefed up the doing and downplayed our previous emphasis on telling and knowing. A visit to the Positive Deviance Initiative headquarters at Tufts University in summer 2009 convinced me that we were on the right track. Now we could begin a new and deeper inquiry and trust that hidden solutions would reveal themselves.

Our iterative progress on the Sundays Project was shaped by a process which can be termed as inquiry after inquiry. Over the past seven years (2009 onwards), community members continue to find unique ways to bring the original concepts to life.

A Day in the Life of the Sunday Project

A typical Sundays Project application of the positive deviance process begins with a date and a location being set for discussions between staff, Native Micronesian community members, the HDOE, and the local school staff. Depending on the location of the school that has been identified for intervention, local school staff identify hot button issues relevant to the educational success of their Chuukese and Marshallese students. The staff’s common concerns usually include poor attendance, tardiness, families not participating in school events, children falling asleep in class, and incomplete homework. To the extent possible, we obtain relevant data from the local school to validate these claims. Sometimes it is available, many times not. However, attendance and chronic absenteeism data by ethnicity is almost always available. On the island of Oahu, schools with greater than 10% of Native Micronesian student show chronic absenteeism rates—i.e., more than 15 absences a year—ranging between 10% to a whopping 75% (Hawaii State Department of Education, 2014).

We compile school data on attendance and absenteeism as aggregated “complex-wide” data so that families of students of different ages and abilities from a wide range of neighborhood schools can relate to the problem. In Hawaii, the term complex refers to the area high school (for which it is named) and includes students of all the middle and elementary schools that feed into that high school. We also can make individual school data available should the Sundays Project participants wish to look those over.3 Each participant in the Sundays Project signs a DOE Consent to Release Information so families can review their individual child’s progress reports and report cards. The parents use this individualized information to discover positive deviants (PDs) in the student pool, assessing the linkages between attendance, absenteeism, and academic performance.

In a 2014 meeting, the Sundays Project presented the following problem statement: Within the McKinley Complex, 44% of all Native Micronesian students are chronically absent. It was further noted that only 18% of non-Micronesian students are chronically absent. This juxtaposition created the container to discuss why, on average, Micronesian students are 2.5 times more likely to be absent than the non-Micronesian ones.

Consistent with the PD focus on investigating what is working, the problem statement was flipped—i.e., Within the McKinley Complex, 56% of Micronesian students are attending school regularly. Who are these students and what enables them to attend regularly? Participants can look at data and identify potential PDs, creating the foundation for discovering what enables them to attend regularly and achieve academic success.

Next, Sundays Project staff, especially those hailing from Chuuk, the Marshall Islands, and Palau, create a plan to recruit Native Micronesian families based on their knowledge of the local people and resources. Former Sundays Project graduates help to recruit new families. Churches, community leaders, and parents help as well. FC staff tries to seek approval in advance from local homeless shelters (they often house significant numbers of Native Micronesians), housing complexes, and Welfare-to-Work programs to ensure that participants can earn credits for community volunteering. Many need eight or more hours per month of volunteer time to be in good standing with the local housing authority. Staff and volunteers go door to door broaching the problematic issues, recruiting family members to join a Sundays Project cohort and commit to a slate of 12 to 15 weekly meetings. Aunties, uncles, grandmas, mothers, and fathers are all welcome. Former graduates provide testimony during community and church meetings to amplify the importance of family engagement. Schools send flyers home in three languages so the students could in turn share with parents and family members.

Once a space is identified for family members to meet, we welcome others to attend and participate. Sometimes parents from various other ethnicities (Thai, Filipino, and Samoan) attend the Sundays Project meetings, as do DOE staff, other service providers, and housing authority staff. While those that miss more than three sessions may not “graduate” with a Sundays Project certificate and T-shirt, they are invited to attend all upcoming sessions. Opportunities for makeup sessions are available and often taken. It is not uncommon for former graduates to return again and again. When asked why they are back, one usually hears: “I learn something new every time”, “I have forgotten some things and need to refresh my skills,” or “I miss my Sundays Project family.” This inclusive philosophy of circular growth is purposeful. Former participants add to the pool of pro-educational PD behaviors through their own lived experience and narratives. As participants identify new solutions, the solutions pool grows to accommodate and celebrate diversity. This inclusive process also creates a core group of community members who become champions of student success, and visible advocates for the Native Micronesian community.

Each Sundays Project session begins with a prayer created by participants and staff together. Available in Chuukese, Marshallese, and English, the prayer goes as follows:

Lord, grant us peace today.

Grant us wisdom to know our value in the lives of our kids; Give us strength to pick up where we left off;

Grant us courage to change for the better;

Accepting hardship as a pathway to peace and success; Trusting in you to help us make things right.

In Jesus’ name. Amen.

While prayers raise eyebrows in public settings, for Native Micronesian families their faith is an integral part of their lives. Important meetings start with thanking God for bringing participants to the table. To meet HDOE requirements of keeping religion out of education, and yet being respectful of the Native Micronesian community, each session officially begins after the prayer has been said. The ritualistic prayer represents the first step in building trust among participants, helping the group understand why they are together—that their own children are struggling to succeed in school. Further, by emphasizing the doing and not just the knowing, the prayer affirms the belief that collective progress is possible with existing resources and strengths.

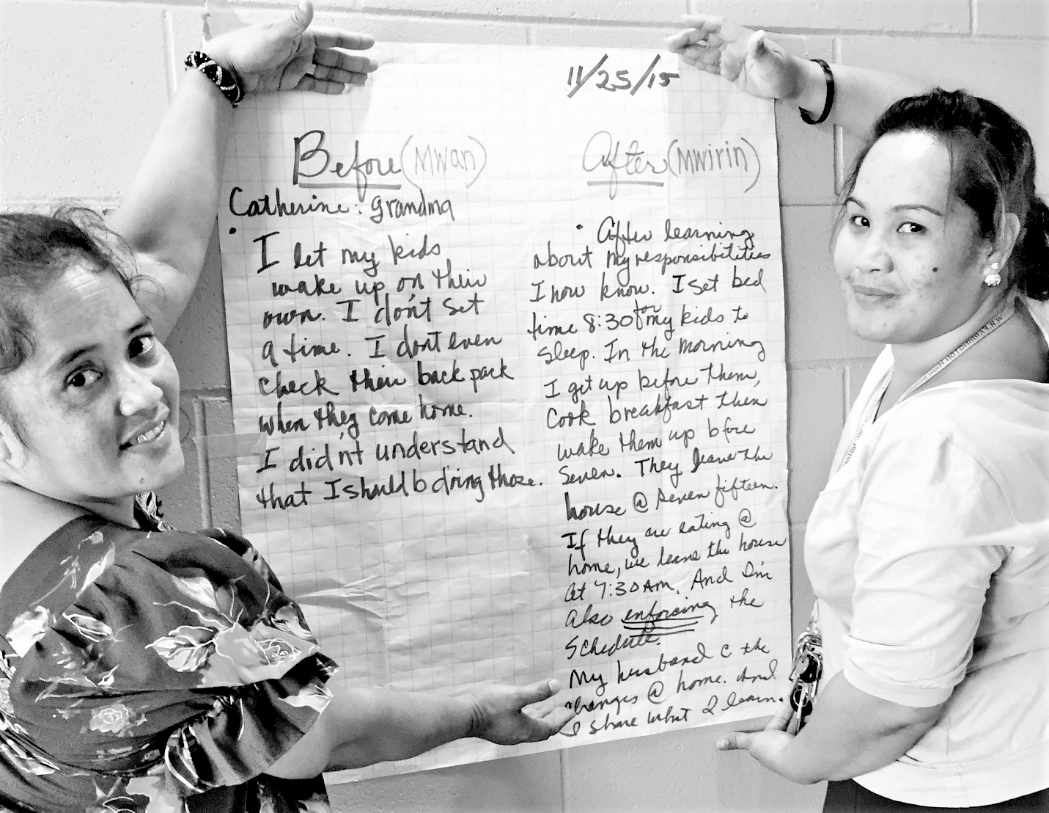

After the prayer, the 2.5-hour Sundays Project session begins with a discussion of the day’s agenda. The agenda is guided by a previously-identified exploration theme. As part of this exploration, a substantial amount of time is taken to discuss Mwan/Mwirin and Mokta/Elikin (before and after in Chuukese and Marshallese, respectively) so participants can share what new behaviors they may have tried at home, and with what outcome (Photo 1). No matter the outcome, the group affirms the genuine attempts made toward change.

Photo 1. A mwan-mwirin (a before-after) discussion in which Sundays Project participants share what new behaviors they tried at home to help their children succeed, and with what outcome. Source: Personal files of the author, used with permission.

The context of these conversations is distinctly Chuukese and Marshallese. For example, one mother talked about putting her children to bed by 8:30 p.m. on week nights—an attempt at a new behavior. She tucked them into bed, turned on traditional relaxing Chuukese music, and gently rubbed coconut oil on their faces and arms for relaxation. Sometimes she narrated traditional stories to her children in bed. Discussions occur on what behaviors are transferable and they are noted on a poster board and taped on walls for all to see. This sharing takes place in Chuukese, Marshallese, and English with translations as needed. These discoveries of successful practices continue to grow cumulatively over time through collective sharing of experiences.

The energy and pride associated with “we have our own solutions” is palpable in these sessions. Almost all sessions tend to end with singing of traditional songs. And, it is not unusual for participants to spontaneously erupt into an improvised dance. (Photo 2)

Photo 2. A dance celebration of change from within—proud participants of one of the first graduating classes of the Sundays Project, 2009. Source: Personal files of the author, used with permission.

One example of an exploration theme may be “Help your child make the most of the school homework.” Questions posed to the group might be “Do you think homework is important?” “Why do you think a teacher assigns homework?” “Do any of you have children that complete their homework daily? If not, do you know of a student that completes their homework daily?” “How does that occur?” “Walk us through what we might see if we peeked in on your child doing their homework daily.”

Families share what they believe enables a child to carry out homework tasks—a quiet place to do homework; the importance of a school planner in organizing work; having pencils or pens readily available; preparing the backpack the night before so homework is organized and more likely to be turned in; the child doing their homework in the kitchen area as a parent cooks dinner; and so on. For younger students, someone may raise the importance of regularly attending to the communication log between a parent and teacher. This then lead to discussions about checking backpacks, how to tell when your child is not being completely honest about completing their assignments, and what to do when your child does not do their homework. One topic may lead to another, to yet another. Asking the follow up PD question—Do you know anyone who is already successful at this?—is vital for identifying transferable PD behaviors (Table 2).

Table 2. Typical Behavior Shifts as a Result of the PD Process Employed in the Sundays Project. 4

| Typical Pre-Sundays Project Behaviors (Before) | Typical Post Sundays Project Behaviors (After) |

|---|---|

| Children come and go from homes as they please facing few or no consequences for their behaviors. Parents feel stressed because they cannot use corporal punishment in the U.S. Many feel they have few tools to control their child’s behavior. | Families create (and some post in a prominent place) a household schedule, following through with behavioral consequences, as warranted. They add and take away privileges according to the child’s behavior. |

| Parents do not ask about the child’s school day. | Parents ask about their child’s school day. |

| Parents avoid going to the schools and feel the school staff are the sole educational experts. Many are very shy to approach school staff. | Parents contact the teacher or counselor regularly to discuss their child’s progress. Parents attend parent- teacher-student conferences. |

| Parents allow children to sleep whenever they please. Many did not realize the important of enough sleep. | Parents get their children to bed earlier. Many enforce curfew with teenagers. |

| Children determine their screen time exposure as they please. | Parents limit TV/computer/phone time. |

| Parents do not understand the expectation of paper- based (or letter-based) communication between teachers and the family. | Parents check their child’s backpack regularly, signing reading logs, planners, etc. |

| Overcrowding leaves few quiet spaces at home for homework to be completed. Parents expect the children to make space for extended family. | Parents set aside a place and time for their children to complete homework, turning off TVs, and limiting overcrowding. |

| Parents yell and speak harshly to their children providing little support for schoolwork and follow through. | Parents speak with more softly to their children and to each other. |

| Parents are traditionally not very affectionate with their children once they are big enough to be in elementary school. | Parents show increased affection to their children and hug them more. |

| In the morning children get ready on their own and walk to school without adult supervision. | Adult family members get up before the children, get them ready, and walk the younger ones to school. |

| Children play in the neighborhood with other children until 8 or 9 pm. Parents are unaware of their whereabouts, nor whom their playmates are. | Children are expected to check in at home after school ends and the parameters of their neighborhood play is agreed upon. Parents ask about their child’s friends. |

| Children accompany their parent on most week nights to choir practice which goes on until 10 p.m. or later. | Parents choose to attend choir practice on weekends only. Or they ensure that someone stays home with the kids so that homework is completed and lights are turned off early. |

| Families are unfamiliar with the resources that are available at public libraries. | Parents obtain a library card, visit the local library regularly to borrow books and participate in story time events together with their children. |

| Parents read report cards with or without a translator. They save them and talk with the teacher about the results. Many provide purposive home supports to help the student improve. | Parents read report cards with or without a translator. They save them and talk with the teacher about the results. Many provide purposive home supports to help the student improve. |

The Sundays Project meetings allow for peer-learning and social proof. Participants feel reinforced about the important role of parents, grandparents, siblings, and others in a child’s educational success. Participants are asked to describe in micro-detail the micro-actions that deliver effective educational outcomes, including how their learnings might be applied to children of other ages. As a consequence, participating adults become interested in learning more about stages in child development, the value of after school programs, the impact of supportive family dynamics, and not being in violation of child abuse and neglect laws.

While the Sundays Project process may not be the classical way to perform a PD inquiry, it worked well for the Native Micronesian community. After 15 weeks of iterative, multi- pronged exploration and experimentation, participating families build up a variety of tools, skills, and capacities for improved family relations and student academic achievement.

In one of our Sundays Project, there were 18 behaviors identified within the community that led to excellent school attendance. These 18 behaviors were described on playing-card size papers in English and Marshallese. The general behavior is shown on one side, for example, families are able to balance church and school responsibilities; and specific family adaptions are noted on the other side of the card, for example, one family leaves all weekday church functions by 7 pm and brings pillows and blankets in their car for the kids to sleep on the way home.

These visually enticing play cards and an accompanying poster, customized for the local area, are made available to family members. Such artifacts, our experience suggests, helps to anchor the discovered wisdom in an accessible manner, creating the enabling and affirming conditions for families, even if at a later time, to practice these behaviors.

Here, in a parent’s own words, we can understand how behavior change occurs through participation in the Sundays Project. I have underlined the various micro-elements of behavior change to make them stand out:

....One day my son’s counselor called to tell me that he has to be suspended from school because of his many absences. I went and asked the counselor to please keep him in school, while I talk to him first and find out what happened. My son told me that his subjects were difficult for him. The counselor worked with him and put him in the afterschool program. She changed his classes to match his learning level. He is more interested in his work now. I happily check his homework every day. When I read his report card this quarter I was happy to see good grades. I praised him. I’m using positive attitude and language with him now.

Upon reading the quote carefully, one notices there is behavior change occurring on the part of the counselor, the mother, and the student. The counselor worked with the mother and delayed their decision to suspend the child whilst the mother investigated the situation. The mother was willing to work with the child to create a success plan based on his ability, and enroll him in an afterschool education program to take advantage of tutoring, social connections, and language enrichment. The student began to attend school regularly, completed his homework daily, and then had it reviewed by his mother. He also began to talk to his mother more openly about his struggles in school. What is important to note is now the school staff, the parents, and the child are working together for the student’s success. And, all parties feel more supported and reinforced to collectively realize their common purpose.

It is interesting that initially parents labeled their children’s behaviors as “naughty”, or “they misbehave,” or “they just don’t listen.” However, over time, the conversations in the Sundays Project sessions shifted from blaming children, to taking collective responsibility. Parents increasingly realized that by changing their own acts their children can be put on the academic path of success.

The graduating family members of the Sundays Project earned a certificate of achievement and a T-shirt—both symbolic badges of honor. Prior to graduation, each honoree completed a pon—a pledge to their families to continually create the enabling conditions for their wards to succeed in school (Photo 3). Interestingly, the use of the pon was suggested by participants themselves—it is the traditional way in which Native Micronesian members of a church make commitments to a deacon, a pastor, or to their family. In the Sundays Project, the participants write out the pon in their own hand and have it witnessed by another peer. The pon is a publicly-made commitment to themselves, their family, and all witnesses at the graduation ceremony.

Photo 3. A pon (pledge) made by a Chuukese graduate of the Sundays Project. It notes in their own handwriting: (1) my children will go to bed at 8:30 p.m. the night before all school days, and, (2) every day I will check my children’s backpacks for homework and letters from the school. Source: Personal files of the author, used with permission.

Moving the Needle

In the Sundays Project, measuring change in family behavior has been relatively easy compared to assessing community-level changes. With a constant influx of newcomers into our communities, and the moving out of families from our service areas, our attempts to measure community-level changes feel like tracking the trajectory of a fast flying arrow. However, by 2016, the Sundays Project graduated over 300 participants in 17 cohorts and hosted more than 2,000 people, including educational professionals, social services providers, parents, pastors, and others. Many attendees simply stop by out of curiosity.

There is plenty of social data available from teachers, principals, and families that point to the effectiveness of the PD process. Much of our work has been carried out in the lower Kalihi area of Honolulu. Fern Elementary, the K-5 school that is closest to the neighborhood where we intervened, boasts a regular student attendance rate of 67%. However, the average daily attendance for Native Micronesians in Fern Elementary is a whopping 96%. In the five surrounding elementary schools, the average, pooled regular student attendance rate was 41%. For Native Micronesian students, the average daily attendance rate was again a whopping 89%. According to HDOE officials, there have been no special programs targeting Native Micronesian students or families at Fern, except the Sundays Project. Did we randomize communities to claim causation? No, but all concerned stakeholders acknowledge the relationship between the Sundays Project and this positive anomaly.

Further evidence of the effectiveness of the Sundays Project comes from HDOE’s Longitudinal Data on chronic absenteeism at Linapuni Elementary School. With the highest Native Micronesian student population (52%) in the State of Hawaii, the chronic absenteeism rate for Micronesian students in Linapuni Elementary was 22.6%, compared to 41.1% for the non-Micronesian students. Typically, chronic absenteeism rates of Micronesian students in other elementary schools in the State of Hawaii are an exact mirror opposite of Linapuni’s numbers. What may explain this result? Linapuni Elementary has hosted three Sundays Projects on its campus to date, with four Sundays Project held within a two block radius of the school. No school faced higher challenges than Linapuni, and correspondingly received higher doses of the PD intervention, and the results are there for all to see. A school-wide PD project is now underway at Linapuni with the overall chronic absenteeism rate dropping from 39% in 2011-12 to 13% in 2015-16.

To implement our Sundays Project, we were lucky enough to cut our teeth on a Federal Department of Education, Office of Innovation and Improvement grant to establish a Parent Information and Resource Center. This funding supported the initiation of the project and allowed it to grow and be evaluated until 2010 when funding was slashed across the country. Fortuitously, we noticed that those families in attendance at the Sundays Project seemed to show improvements in their general parenting skills and a decrease in domestic abusive practices. They were also quicker (relative to their peers) to pick-up acculturation skills. Further, many graduates went on to obtain better jobs or seek more educational opportunities to support their families. These observations allowed us to make a stronger funding argument that the Sundays Project could be used to improve family engagement in education, to curb child abuse and neglect, and support acculturation and job skills of new immigrants through the volunteer opportunities we offered. And, in so doing, we could intervene with two or three generations of Native Micronesians at one time. This argument allowed us to obtain funds to continue the program through the Office of Community Service, Hawaii State Department of Education and the Department of Human Services. We believe that the awarding of this grant, in itself, represents a testimony to the multi-pronged efficaciousness of the Sundays Project intervention, including across generations.

The continued funding challenges makes us increasingly rely on the Native Micronesian families themselves to maintain, sustain, and amplify the good work. Many Chuukese and Marshallese host new family members coming from the Micronesia, and those who have attended Sundays Project meetings have pledged to pass the behaviors forward through family meetings, and through church and women’s groups.

Conclusions

Taking on a social change initiative where at least three languages and multiple cultures intersect, is a daunting enterprise, to say the least. However, our seven-year experience of employing the PD approach in Hawaii to foster the educational success of Chuukese and Marshallese immigrant children demonstrates:

that family engagement and academic achievement go hand in hand.

that the PD approach provides a wholesome container—a philosophy, a framework, an orientation, a structure, and the needed flexibility—to empower Native Micronesians to support their children’s academic success.

that the PD approach helps to open up and greatly expand the solution space. It makes possible for ingenious, indigenous solutions to rise from the ground-up.

that the PD approach allows the culture of the community to stay intact, and this is the most appealing and strongest feature of this method of social and behavior change. Our goal from the very beginning was to shift educational norms among the Native Micronesian community while preserving and harnessing their cultural traditions and assets. PD allows us to find solutions without fighting against the dominant community norms, creating outcome equity where there was none.

While our work focused on educational success in immigrant communities, the PD approach is flexible and versatile enough to be applied to a wide variety of other sectors and vulnerable groups. PD took our project from being an information-transfer process to one where all participants could share their actionable discoveries. These discoveries and behaviors continue to enrich the Sundays Project program, paving the path for more and more Native Micronesian students to find academic success.

References

Agency, C. I. (2013). The World Factbook 2013-14. Retrieved May 15, 2015, from Central Intelligence Agency: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world- factbook/rankorder/2112rank.html

Hawaii State Department of Education. (2014, February 28). Longitudinal Data System. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA: Hawaii State Department of Education.

Heine, H. C. (2002). Culturally Responsive Schools for Micronesian Immigrant Students. Honolulu: PREL (Pacific Resources for Education and Learning).

Jetnil-Kijiner, K. (2013, January 19). Lessons From Hawaii. Retrieved June 15, 2015, from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=18&v=3sbtpazYra0

Levin, M. J. (2015). The Status of Micronesian Migrants in the Early 21st Century - A Second Study of the Impact of the Compacts of Free Association. Harvard University, Department of Public Health. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Moyer, D. (2014, June 13). Chronic Absenteeism in Hawaii Public Schools. Retrieved May 22, 2015, from Prezi: https://prezi.com/my-wo272o5p_/chronic-absenteeism-in-hawaii-public-schools/

Moyer, D. (2015, June 23). Acting Director, Data Governance and Analysis Branch. (C. Simmons, Interviewer) Honolulu, Hawaii, USA.

Office, U. G. (November 2011). Compact of Free Association - Improvements Needed to Assess and Address Growing Migration. Washington, D.C.: USGAO.

Plewe, B. (1996). Oceania/Australia. Retrieved June 23, 2015, from Political Resources: http://www.politicalresources.net/oceania-map.htm

Society, R. (2015). U.S. Nuclear Tests Info Gallery 1945-1962. Retrieved June 28, 2015, from Radiochemistry Society: www.radiochemistry.org/history/nuke_tests/index.shtml

Endnotes

1 I sincerely thank my funders, supporters, and staff at Parents and Children Together; Hawaii State Department of Education; Hawaii State Office of Community Service, Department of Labor; Federal Department of Education; The Chuukese Community; The Marshallese Community, and, The Learning Coalition. This work could not be done without the real experts, the staff members—Kalista Marbou, Merleen William, Rosalinda Gaopoa, and Gloria Lani— whose boundless commitment to the immigrant families is bar none.

2 This is based on a triangulation of data points from Title III English Language Learner data, numbers of Micronesian students graduating in 2015, and the projected number who should be graduating in 2015.

3 It is important to point out that using complex-wide data (in contrast to individual school data) may seem “messy.” However, this allows the possibility to affect a wide range of community participants—from Native Micronesian family elders, to children ready for preschool.

4 Table 2 only lists a handful of identified PD behaviors in the Sundays Project. The stories of how families put these behaviors into practice represent pure gold.